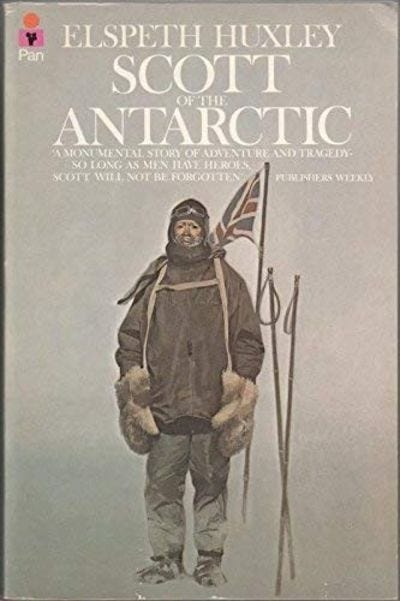

How did Elspeth Huxley come to write one of the best biographies of Robert Falcon Scott in the 1970s? Approaching the age of 70, her literary focus had turned to historical nonfiction, although she continued to meditate on the central motif of her life: the colonial Kenya of her childhood. She wrote and rewrote her memoirs of British East Africa, obsessive in her quest to define the character of the fading empire–and the role of Englishwomen within it.

On the topic of a fading empire: Scott was the subject of great popular interest in late 20th century Britain. Mounting tensions in the Falklands renewed public interest in Britain’s legacy in the Antarctic. Scott’s failure to reach the pole before his Norwegian opponents in 1912 and subsequent tragic death disrupted teleologies of English superiority. Huxley was not the first to be granted access to private materials, writing ten years after Reginald Pound and concurrently to Roland Huntford. Pound had opened a door; by exposing Scott’s personality flaws, conservative commentators had been given a figure upon which to project the maladies of the empire. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that the door had been open since 1912. There are few clearer case studies of a human life being reduced to a symbol at the moment of death in modern British history.

While a zeitgeist of imperial anxiety certainly played a role in Huxley’s project selection, there’s a straightforward answer to the question of why then. According to Huxley’s own biographer, C.S. Nichols, Huxley’s publisher procured a list of five potential subjects for a new book. Huxley picked one, and it happened to be Scott. Huxley had enjoyed a wide readership for her two prior publisher-assigned biographies of Livingstone and Florence Nightingale. Scott would do.

This origin story does not wholly satisfy when one learns that Huxley had been friends with Peter Scott, the explorer’s son, for several years at that point. Her last book would be a biography of Peter himself, published in 1993. Peter, a dedicated environmentalist, was an enormous influence on Huxley’s own thinking about the natural world. In her later years, she was much transformed from the boastful young woman she described in her memoir The Mottled Lizard (1962) who gladly participated in regular cheetah hunts.

Before Peter, Huxley’s moral code as a hunter was simple, a striking sort of inverted chauvinism which made “this blood-lust respectable.” Huxley instructed the reader: “you must not kill females or youngsters; you must shoot only when you felt reasonably sure of killing cleanly; and if you hit an animal you must follow and despatch it…[hunters] merely culled older males– the best heads were normally to be found on fully mature animals – and so kept up the vigour of the breeding stock.”1 Huxley became an avid supporter of Peter’s incipient World Wildlife Fund, protested the practices of farmers in Kenya who encroached upon indigenous fauna, and declared man to be “the most destructive creature of all.”2

While Peter’s influence on Huxley’s environmental ethic is clear, whether he had any part to play in her choice to write a biography of his father–beyond giving the project his blessing–is less transparent. In order to understand what the story of Scott’s life meant to Huxley, we must revisit Huxley’s literature on colonial Africa, which reveals a unique cosmology of gender relations at the heart of empire. First, let’s break down the quote from Scott of the Antarctic that most struck me– indeed, most moved me– and opened up this path of inquiry. In the following passage, Huxley describes Scott’s brief courtship of Marie-Carola D’Erlanger:

All that is known of his courtship are three impressions set lightly in a child’s mind. First: a scene in a London Park on a summer’s day. Marie-Carola was taking her two small children for a stroll. Instructing them, as they sauntered under the trees, in some point of geography, she paused to draw a map in the dust with the tip of her parasol. A blue-eyed man came up behind her, smiled in amusement and lifted his straw hat. Second: the sourness of a French governess whenever she saw Scott’s hat and gloves in the hall. It was not that she had formed a dislike for this particular suitor, but suitors spelled change; she did not want change, and feared as its harbinger the owner of that hat and those gloves. Lastly: after those garments were seen no longer in the hall, a tale of an unforeseen encounter between the two protagonists at a dinner party given by a mutual friend. They did not speak and, when dinner was over, Scott’s linen table-napkin was found torn to shreds and scattered on the floor.3

I confess that I find the “female gaze” to be of limited use as an analytic. Mulvey’s original argument was about the visual tools of objectification. To flip the script and objectify the male subject is not particularly revelatory within the context of the polar biography, a genre that is obsessively concerned with categories of male beauty; the body whole and then broken, martyred for science and country, still redemptively beautiful in abjection or death. If anything, Huxley’s gaze fascinates because it eschews objectification, removing the body from the picture alltogether.

She offers scant descriptions of the subject himself. He is blue-eyed but not so handsome, young and then not so young. All of the explosive claims about Scott’s character that would be sensationalized by Huxley’s rival biographers were present in this volume. But Huxley finds humanity in distance, sometimes absence. Scott exits the narrative of his own life, becomes a straw hat, a pair of gloves, a discarded napkin. The women usually relegated to the periphery of the story– the proverbial French governesses in the hall, eternally observant and laudably sensible– take the reins. This was a conceit that characterized much of Huxley’s historical writing.

Huxley was a proud member of a class of Englishwomen who thrived at the boundaries of the empire. She was the only child of coffee planters who imagined themselves explorers of a new frontier. Brought to Thika by her upper middle class parents at the age of six, Huxley learned to see herself as an explorer too from early childhood, roaming the lowlands unsupervised. White settler women of this generation constructed themselves as people who made do, fundamentally unfussy. While Elspeth’s mother, Nellie Grant, was descended from marquesses, both Nellie and Elspeth affected disdain for the aristocracy in favor of a code of self-sufficiency. During a brief brush with the gentry, Nellie recalled the daughter of a wayward Duke relocated to Nairobi telling her that every night she repeated the same prayer: “Please God don’t make me a Lady, make me like Mrs. Grant.”4

The Englishwoman who thrived in British East Africa was not a product of acclimatization, but rather naturally suited to manual labor on the farm and safari hunts. Huxley constructed the colonial settler woman as an evolution of the aristocratic women of the English countryside, unglamorous but practical, preferring jodphurs to ballgowns. They populate the pages of The Flame Trees of Thika, The Mottled Lizard, and Huxley’s criminally underrated murder mysteries set in the colonies.

There’s an equally important gendered element to Huxley’s body of work: the Englishmen who arrive in Kenya in search of new prospects are usually either ineffectual or dead. Consider Hilary, Robin, and Ian Crawfurd in The Flame Trees, mawkish men all rivaled by the hardiness of their female relatives and lovers. The strangled colonial official, Sir Malcolm McLeod, of Murder at Governor House. The complete absence of non-hostile adult men in The Story of Mary Cornish, which concerns a London music teacher heroically shepherding six boys to safety after their ship is torpedoed in the Atlantic while recounting didactic tales of Nazi tyranny.

Historian Wendy Webster observes a streak in Huxley’s writing which “claims female superiority in [...]masculine arena(s), where women outdo men in qualities of adventurousness, resilience and persistence.” This was a provocative claim in the context of postwar anxieties about the decline of British rule– anxieties intrinsically tied to fear mongering about the decline of British masculinity. Crucially, Webster argues that Huxley’s work does not play into these laments of supposed rampant feminization at the hands of emasculating women. Matter of fact as always, Huxley tells us that this has been the order of things since the incipience of the colonies.5 To Huxley, Englishwomen were simply better suited for adventure than men. They had to be, so far from home. Men could live in the realm of idealism, but their pipe dreams fell through in the face of their inflexibility.

Let’s flash forward back to the 1970s. Britain was swept up in a wave of imperial nostalgia, and every prominent literary voice seemed to have a stake in the debate over the root cause of waning British rule. Revisiting Scott’s failure seemed to hold the key for many. Reginald Pound found the very ideal of the Edwardian man of action in Teddy Evans, the naval lieutenant who clashed with Scott but later emerged as an unlikely war hero and politician. Upon being granted access to Scott’s private sledging diary, Pound encountered a Scott who seemed to stand in opposition to all of Evans’ ascribed virtues. Scott was temperamental, indecisive, overtly-emotional. Writing in the exposé style, Pound wondered whether Scott was the canary in the coal mine, predicting the state of postwar English masculinity. Roland Huntford, Scott’s most widely-read biographer, would repeat this assessment a decade later. In his dual biography of Scott and Amundsen, Amundsen emerged as a he-man with incorruptible morals while Scott was effeminate, dominated by his independent wife Kathleen. Both literary efforts ring hollow. Elspeth Huxley, on the other hand, was characteristically genre-aware. She knew that there was no masculine ideal; only men. Getting to know one of them intimately means getting to know them thorns and all. A kind of boyish naïveté allowed her contemporary biographers to assume that there were no thorns, leading to disillusionment– perhaps they could have benefitted from some time in a lifeboat with Mary Cornish.

Here I make no claims of essentialism, no argument that women write men’s biographies better because they are innately free of chauvinist hero-worship. Rather, I believe that Huxley’s forging within the fires of a colonial feminine sensibility gave her a unique perspective as a biographer. It was a book only she could write. There’s an appealing combination of intimacy and distance laced through Huxley’s Scott of the Antarctic; the same hardy, no-nonsense attitude Huxley adopted during her youth serves her well as a narrator. Let’s turn to her assessment of another hero of the Terra Nova expedition, one equally reduced to myth. Captain Lawrence “Titus” Oates is best known for his decision to walk out of the tent into a blizzard on the fatal final stretch of the sledging journey back from the Pole. While Pound and Huntford both offered the conjecture that Oates must have been pressured by the tyrannical Scott to make this choice, Huxley offers a sobering reading of the same event:

‘Titus’ Oates kept his motives hidden. And the destruction of his diary ensures that so they will remain. He was bored with army life, he sought action, he shared the thirst for adventure felt by many young men of his time and class. He had no need to seek a fortune, which in any case did not interest him, and it is most unlikely that he sought fame. A certain gruffness of manner, a dislike of society, a contempt for women (other than his mother, his friend and confidante), an obsession with sport involving animals and animals themselves, all these suggest some inner injury or apprehension, a disillusion with himself and the world. In going to the Antarctic– he was desperately anxious to be chosen– he was perhaps running away, to seek in that austerely male companionship a sanctuary from the complexities of the civilised world. Of his leader he expressed few opinions, apart from irritation when the Captain tried to balance his need for coal against that one for pony-fodder. He was a lone wolf. His last act was a fine one, but hardly one of self-sacrifice; he was already done for and knew it, and to walk into a blizzard seemed a fitter way for a soldier to die than to swallow the opium tablets in his wallet. Oates remains an enigma, which is no doubt what he would have wished to be.6

To me, this passage exemplifies the possibilities and limits of heroic biography. Huxley makes an effort to understand a figure reduced to patriotic aphorism as a fully realized human being, a product of his times, both marvelously unique and much like the other young aristocratic men of his generation. Even Huxley’s brief forays into psychoanalysis feel justified– of course someone molded by the rigid world of the Edwardian military would suffer injury and apprehension. Pound and Huntford, on the other hand, could only consider Oates from the hagiographic angle. Humanity would interfere with the ideal, make the romantic tragedy feel too much like a real tragedy that teaches us nothing, and was to be weeded out from the narrative judiciously.

Huxley was adept at explaining the historical trajectory of these mens’ lives, but more strikingly, she was comfortable with the enigma of the human heart. Returning to the subject of Scott’s infamous insecurities, Huxley wrote:

Scott had grown over-touchy. At this stage of his life a demon was sitting on his back and marriage had made it worse instead of better. What was the trouble? Self-mistrust, self-contempt, almost self-hatred: these were apparent. What lay beneath? ‘Con dear are you still and always an unhappy man?’ Kathleen [Scott’s wife] asked. ‘Oh what’s the matter Con? What is the matter?’ He could give no answer, although he searched for one in the recesses of his mind and heart. ‘What does it all mean?’ is a sentence that often occurred in his letters. If he could give no answer, no one else can.7

Huxley does offer a possible answer: he compared himself unfavorably to his indomitable wife, the sculptor Kathleen Bruce. Rebuked as mannish, “athletic”, even “vaguely bisexual” by Roland Huntford–who accused Kathleen of infidelity based on scant evidence–Kathleen is an eternal question mark in Scott biographies. Exceptional women in the historical record usually see themselves as exceptional rather than subscribing to palatable modern constructs of sisterhood. Kathleen fit neatly into this category, shunning the company of women and preferring the world of men and making her rather difficult to champion as an aspirational feminist figure. She made her own living and traveled the world over by herself, but she also relished in her lack of emotional attachments. In her diary, she described her inability and unwillingness to weep over her husband’s death even though her doctor prescribed weeping. If she was alien to other polar biographers, to Huxley, Kathleen was rather familiar. Kathleen’s unsentimentality in widowhood recalled the pioneering women Huxley grew up with.

Furthermore, Huxley recognized Kathleen’s resolve without diagnosing any effeminacy in Scott as contrast:

The lot of a sailor’s wife in those days was generally pitied, with her husband away at sea for perhaps nine-tenths of their married life while she was left to bear the brunt of maintaining the home, rearing children, and enduring the loneliness of separation. The man, by contrast, was away in his ship having a rollicking time among his chums, carefree, well looked after, probably with wives in other ports. This was the popular image. For Con and Kathleen, the reverse was true. It was he who was lonely in his captain’s solitary splendour in the Bulwark, she who was living it up among a host of friends in London as well as beginning to make a name as a sculptor. 8

Huxley avoided romanticizing the Navy by acknowledging the alienation possible in a masculine life at sea, while poking holes in the myth of feminine passivity. Huxley also worked against the fashionable understanding of the domesticated British male of the 19th century, an argument requires further unpacking in the context of exploration. Historian Martin Francis has called for Victorian masculinity studies to acknowledge how “men constantly travelled back and forward across the frontier of domesticity [...] attracted by the responsibilities of marriage or fatherhood, but also enchanted by fantasies of the energetic life and homosocial camaraderie of the adventure hero.”9 Huxley takes it further, elucidating the specificity of her subjects’ attitudes towards domesticity and, crucially, highlighting Kathleen’s utterly undomestic nature. Kathleen’s adventurous agency elevated her to a protagonic role in her own life– and in Scott’s life, by turn.

I picture Kathleen in her studio in 1917, working on one of her many commissioned statues of the late Scott. She recreated his his image as one that would be palatable to the public, with marble she had carved from the quarry herself in Italy. In the void left behind after Scott’s death, she rose to fill the space. Like Kathleen, Huxley does not fit neatly into feminist literary analysis. Crucially, her biographical project was just as influenced by a sense of imperial nostalgia as Pound or Huntford. Huxley’s later advocacy for Kenyan independence reflected her unwavering belief in the potential for English acclimatization– to her, the tyranny of colonial rule had lain in faulty execution. Huxley’s identification was not with African Kenyans, but a class of female colonial explorer who existed at the edge of possibility, mutable and hardy. It’s a conservative understanding of what a woman’s work is good for– in this case, for the improvement of the nation, its moral fiber. And yet, Huxley’s treatment of the male vs. female hero still excites. There is a knowing delight as she pulls the strings of the narrative. Here, too, she seems to say, a woman is in control.

Huxley, Elspeth, The Mottled Lizard. London: Chatto & Windus, 1962. p. 265

Interview with Elspeth Huxley, Sunday Telegraph Magazine, 9 March 1980

Huxley, Elspeth, Scott of the Antarctic. 1st American ed. New York: Atheneum, 1978. pp. 156-157

Nicholls, C. S. Elspeth Huxley: A Biography. London: HarperCollins, 2002. p. 65

Webster, Wendy, “Elspeth Huxley: Gender, Empire and Narratives of Nation, 1935-64,” Women's History Review, 8:3, 527-545. 1999.

Huxley, Elspeth, Scott of the Antarctic. p. 271

Huxley, Elspeth, Scott of the Antarctic. p. 177

Huxley, Elspeth, Scott of the Antarctic. p. 174

Francis, Martin. “The Domestication of the Male? Recent Research on Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century British Masculinity.” The Historical Journal 45, no. 3 (2002): 637–52.