I asked her why she felt impelled to pit her feminine strength against piercing winds, thin air, ice hazards, and all the other dangers of trying to conquer one of the sister peaks of Everest. She answered simply: “Because I like it.”

–Stephen Harper on Claude Kogan, in A Fatal Obsession: The Women of Cho Oyu– a Reporting Saga1

There was something decidedly chic about them. The members of the Women’s Expedition to Cho Oyu included the wife of an exiled Italian Count, a former companion to a Luxembourgian Princess, and the headmistress of a secretarial college for girls, tucked away in a stylish suburb of London. In Kathmandu, they were joined by two daughters and a niece of the famed Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, the man who had completed the first summit of Everest alongside Edmund Hillary six years prior.

Claude Kogan, the expedition’s leader –French, 4 feet and 10 inches tall– moonlighted as a designer of women’s swimwear. The press was equally scandalized and intrigued. No consensus could be reached as to whether these were the sort of women one expected to climb mountains or not. But the more I dig into the lives of the nine climbers who attempted the first all-female summit of Cho Oyu– the members of L'Expédition Féminine de 1959 au Népal– the clearer it becomes that these women thought of themselves as mountaineers first. Their fashionable civilian pursuits were temporary personas they could slip into while their hearts were set on distant peaks. Two of the women would end up paying the ultimate price for their aspirations.

Daily Express reporter Stephen Harper, who would go on to publish a full-length book on the expedition in 2007, recalls meeting Margaret Darvall (the expedition’s most experienced English delegate), who reclined “in a summer dress among the chintz chair covers” of her Hampstead girl’s school.2 He had been assigned to cover the climb, a tricky proposition as Claude was very clear: no men were to accompany them up the mountain. Harper was as mystified and beguiled by the women as the rest of the press; they were curiosities.

When he asked Darvall how she caught the climbing bug, she replied, “I climb mountains because it is so different from my ordinary life. It’s an escape for me.”3 Loulou Boulaz, a shorthand writer at the United Nations, told Harper: “I like the excitement that the dangers of climbing provide.”4 Harper’s book is, in and of itself, a baffling source; opaque, a puzzle box through which we see the fateful sequence of historical events that unfolded on the mountain filtered through the perspective of a male journalist, who slowly becomes aware that the women around him have conspired to present him with an incomplete version of the truth.

The combination of thrill-seeking and ambition can lead you to dangerous places. The Expedition’s raison d’être can be traced back to Claude Kogan’s 1954 attempt to summit Cho Oyu. It was a notoriously difficult climb, as well as one of the most beautiful. The summit forms a plateau, from which those who are both very determined and very fortunate can look to the West and, in the glorious alpenglow, see the entirety of the Khumbu region of the Himalayas stretch out before them: Makalu, Lhotse, Everest. Even the mountain in this tale takes on a feminine quality: Cho Oyu translates to the “Goddess of Turquoise” in Tibetan.5

During her first encounter with the Goddess, Raymond Lambert, Claude’s male climbing companion, forced her to turn around just 450 meters from the summit. In one of the few pieces of published writing Claude ever produced, she recounted the sordid scene:

I felt myself boiling with impotent rage, ready to dare anything if we could continue with the struggle. Although my reason saw it was the only logical decision to take, my heart refused to accept it. I didn't wish to bow my head before the wind and snow that must eventually hurl us back. "Don't turn back yet,” I gasped.6

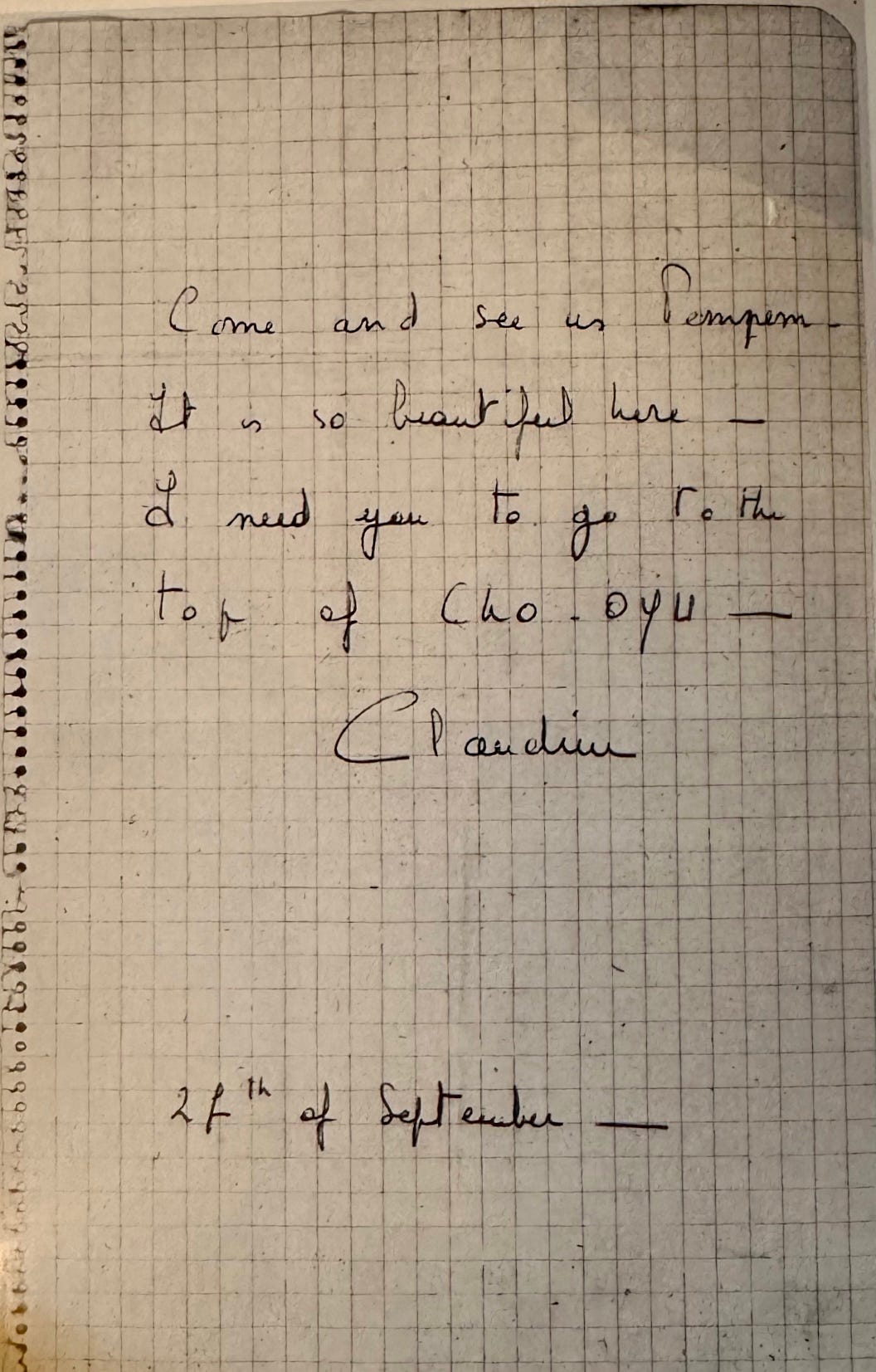

So she made up her mind: to preclude the interference of male opinion, Kogan would organize her own all-female expedition. The objective was once again Cho Oyu. By the end of the year, Claude and Claudine– her second-in-command– would die in an avalanche on that very mountain, along with two Sherpas, Ang Norbu and Chewang. They had only surpassed Kogan’s prior attempt by 50 meters. Their bodies were never found.

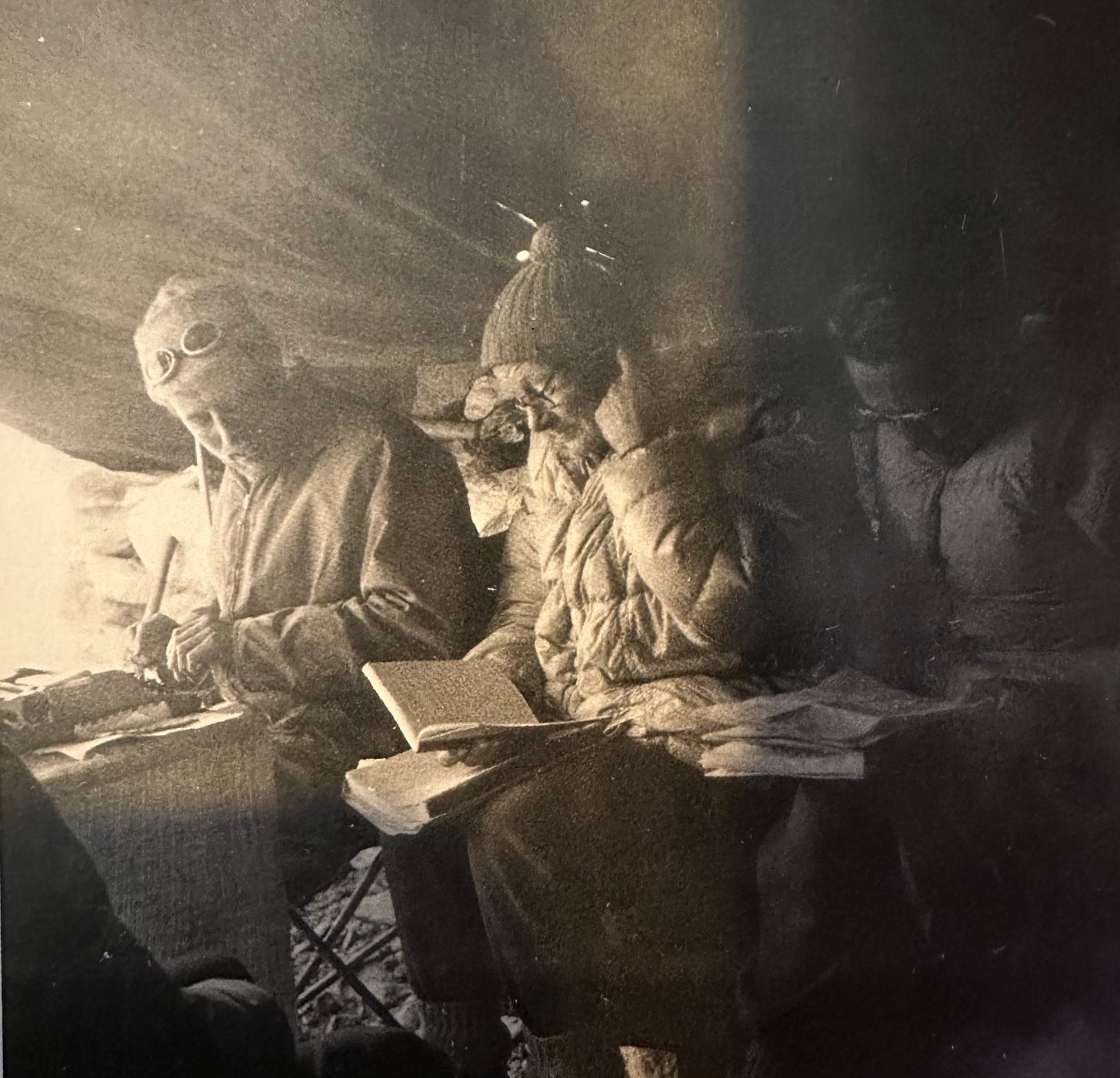

We know little of what transpired during the two women’s final push to the summit from Camp Four. They communicated with expedition members back at base camp via handwritten notes dispatched through a rudimentary rope delivery system down the mountain. Claude and Claudine often clashed, and we can’t know whether they resolved their differences before they died together, or whether the decision to stick it out at the last camp with little support as a blizzard approached was reached unanimously.

Though she worked as a couturier at her Parisian swimwear boutique, Claude’s personal style was tomboyish and devoid of vanity. She was known for her iron will and sharp tongue. Perhaps there was a more sentimental side to her; she was one half of a great love story. Claude had met her husband during the German Occupation of France while climbing La Baou de Saint-Jeannet as a teenager, where she found the Russian-born Georges Kogan taking refuge from the Gestapo in an abandoned chalet. She snuck him a portion of her rations until his capture, although the two were shortly reunited due the timely arrival of Allied forces. They worked in fashion together, and climbed in the Andes until Georges’ death in 1951.7 After his passing, Claude left a photograph of her husband along with a silver brooch at each summit she reached. Male observers she came into contact with in the press pool and in climber’s associations, however, often found her strange, improbable, and icy.

Claudine van der Straten-Ponthoz, on the other hand, was a media darling– and she relished it. Born into the Belgian aristocracy, Claudine had spent some years as a courtly companion to Princess Charlotte of Luxembourg. Like the other women, however, she thought of herself as a mountaineer. At twenty-six, she was an accomplished skier and Alpinist. Claudine had first met her future expedition leader not in their native Alps but in the Andes, when she climbed Cayesh in Peru alongside Claude and Raymond Lambert (who must have briefly made it back into Claude’s good graces).8

Claudine was perceived as the most conventionally feminine member of the group– reporter Henry S. Bradsher felt the need to comment that she was “the only beauty in this hard-bitten bunch.”9 She had a distinctive blonde poodle cut, and a penchant for gold lamé leggings. The first signs of conflict with Claude emerged when the expedition leader threw Claudine’s cosmetics out of her luggage before the pair left Paris, with Claudine complaining that “all she left me was the red nail varnish because she said that might be useful in marking numbers of loads.”10 While Stephen Harper was not exactly the most reliable narrator– especially when Claudine was concerned– he recounted a cocktail party at the British Embassy in Kathmandu, where Claudine confided that she “dread[ed] the thought of the approach march, and having nobody but women for company.” When further pressed, she quipped: “For me, having no men has no advantage. I don’t like responsibility anyway.”11

Do these comments reflect Claudine’s attitudes towards traditional gender roles, or do they speak more to her political savvy, honed in a world of barons and princes? After all, why would she climb Cho Oyu–a matter of life or death–if she could do without it? Part of what makes the prospect of deconstructing the mythos surrounding L'Expédition Féminine both appealing and maddening is the scarcity of first hand accounts written by the women.

There is Jeanne Franco’s brief testimony, published in Le Monde upon her return to France (although the framing is sensationalist and oddly glamor-filtered, the reporter recounting how Jeanne, with inexplicably “glistening skin” throws herself into the arms of her husband while weeping profusely).12 There are snippets of Countess Gravina’s journal, detailing her attempt to recover her superiors’ bodies. And, in the process of researching this article, I learned that Micheline Rambaud–one of the expedition’s two filmmakers–published a companion memoir to the documentary footage she released in 2022, titled Voyage Sans Retour.13

However, it is Eileen Healey–member of the British delegation, bacteriologist, and filmmaker– who emerges as the leading first hand witness due to her collaboration with Harper on the publication of Fatal Obsession. Even then, the narrative takes on a Pale Fire-esque quality; reading A Fatal Obsession presents an exercise in parsing layers of truth and fiction, as Harper first acquired access to Healey’s rigorous expedition diaries half a century after the expedition. In real time, Harper learns about the full context surrounding key events in the course of the expedition that he was denied access to– including the brief coverup of the womens’ deaths, orchestrated by the survivors at Base Camp in the days following the fatal avalanche.

In retrospect, there were hints that Harper was not wanted. During an early exchange, the Countess Gravina (“smugly”) informed Harper that “Madame Kogan and I have seen the Prime Minister. We have no problem with you or any other newspaperman visiting the mountain. You will be refused permission to visit the area on grounds of the critical frontier situation.”14 The Daily Express flag, so enormous that it was confiscated by Indian authorities, was never to see the summit of Cho Oyu. Harper would cover the expedition from Kathmandu.

Darvall explained: “We don’t want a man anywhere near us because people will only belittle our achievement by saying there was a man standing by in case we got in trouble.”15 During their brief time together in India and Kathmandu preceding the approaching march, the pan-European crew would form a linguistic alliance against Harper: “The ladies were by this time pulling my leg a lot, and there was rapid banter in French about which one of them should room with me!”16

Tensions came to a head when Harper made his return to base camp on the previously agreed-upon date to receive news of the ascent’s success or failure. In a questionably titled chapter, “Women’s White Lies”, Harper recounts a bleak approach across a “lunar landscape of grey moraine, blue ice cliffs and a profusion of giant boulders”, the silence punctuated by the staccato rhythm of rocks thrown by runners– Sherpas who ruled the low-altitude trails leading from the populated Namche area up to the Himalayas, employed as messengers by competing teams of mountaineers, yeti hunters, and reporters.17

Harper had grown impatient with the women. They had promised to send Harper regular reports, but Harper had only received radio silence for some time. Two runners carrying the first dispatch from the women in over two weeks refused to pass over any news to Harper, claiming they had been tasked to speak to no one but the two “memsahibs” awaiting them back at the nearby outpost of Namche Bazaar– presumably one of them was Margaret Darvall, who had stayed behind.

Nearing the end of his rope, Harper wrote a strongly-worded note to Gravina– who was left in charge of the camp as the leading pair took on the summit– that threatened legal action. More and more runners came, and the story started to come together, piece by piece. Harper had experienced the monsoon weather of the past week personally, although at a lower altitude it took the form of unpleasantly heavy rainfall. Harper did not know quite how bad the atmospheric effects had been, triggering terrible blizzards and subsequent avalanches up on the peaks. Harper was informed of one such avalanche on Cho Oyu by another pair of runners, who claimed that one of the womens’ hired Sherpas– Chewang –had been swept away and killed. They reported that Claude and Claudine had returned to base camp safely. But there were rumors spreading on the trails: the two women might still be missing.

Harper decided to first return to Namche Bazaar and consult Darvall. She repeated the same story about Claude and Claudine making it back to base camp between the raging blizzards. There is a revealing comment from Harper that provides insight into assumptions of Western vs. regional expertise, the testimony of a female European climber vs. that of the Sherpas: “I had enough experience to know how wildly inaccurate Sherpa accounts could be, and I also felt that because of my special position with the expedition I had no alternative but to accept what the women told me.”18

However, Darvall soon broke down. “As I was about to leave,” Harper recounts, “Miss Darvall suddenly put her head in her hands, and said rather desperately that she was in an awkward position. Then it came out in a flood.”19 Claude and Claudine had been missing for a week, and were presumed dead. The survivors had decided to withhold this information from Harper so that the families–including those of the Sherpas– could be informed before the headlines came out.

Darvall, Gravina, and Healey had all conspired to prevent the story from breaking too soon, both of a genuine sense of duty to their departed leaders and as a way to do damage control regarding the reception of a failed all-women’s expedition. Martina Gugglberger, one of the only scholars who has worked with Healey’s Cho Oyu diary (or indeed, written about the expedition at all) notes that there is something of a key change in Healey’s writing when Claude and Claudine went missing. Gugglberger notes: “Healey avoided any comments or emotional expressions, which can be explained by the fact that her notes had no private character but were written in the knowledge that they had to be made available to the press.”20

Additionally, there are moments in A Fatal Obsession where Harper explains through footnotes that at the time of writing the book 50 years later, he was still piecing together Healey’s half-truths. At the same time, Darvall and Gravina corresponded with Dorothee Pilley-Richards, one of the founding members of the Pinnacle Club, who blamed the failure on the “fanatic” fervor of Claude’s decision making, and warned the women to say nothing to the press.21

The aftermath of the Cho Oyu tragedy played out exactly the way Pilley-Richards expected it to. The headlines were sensationalist. The damage was done to the reputation of female mountaineers the world over– it was a typical example of women facing extra scrutiny when entering a male-dominated field, any challenges or failures being taken as a sign that it was never meant to be. Gugglberger notes that one of the obituaries of Claude Kogan was rather cruelly named “The Mountain is still the Master.”22 This is a marked reversal of earlier narratives of male climbers in the Himalayas, which were laced with gendered erotic imagery of nature’s ravishment. Cho Oyu was no longer a goddess waiting to be conquered via chauvinistic shows of strength, but a dominating masculine entity that had successfully tamed the shrew.

I believe that it is important to relay this little-known story from the history of mountaineering to a new audience; but I don’t want to merely narrate the Women’s Expedition, or suggest that we can uncritically reclaim this episode as a feminist story. I want to interrogate what this story meant to me, why it fascinated and affected me so entirely when I encountered it by chance for the first time about a year ago. Why does the narrative constructed around the expedition land the way it does? What are the broader issues of identification and representation at play here? And what changes when we talk not only about female adventure narratives, but about female tragedy?

One thing the Women’s Expedition has the potential to do is disrupt the way male vs. female propensity towards high-risk activities is commonly discussed. Many well-intentioned voices are eager to call upon the notion of an innate feminine sensibility, standing in opposition to men’s stupidity when criticizing male-dominated fields such as exploration and athletics. Regarding this topic, Ursula K. Leguin said it best:

“But I didn’t and still don’t like making a cult of women’s knowledge, preening ourselves on knowing things men don’t know, women’s deep irrational wisdom, women’s instinctive knowledge of Nature, and so on. All that all too often merely reinforces the masculinist idea of women as primitive and inferior – women’s knowledge as elementary, primitive, always down below at the dark roots, while men get to cultivate and own the flowers and crops that come up into the light.”23

Post-facto accounts of the Women’s Expedition tend to highlight Claude’s obsessiveness and fanaticism. But wouldn’t these same traits be lauded in a male climber, reworked into passion and courage? I do think female historical figures should be allowed to be obsessive and fanatical, of course. But I also believe that Claude calculated the risks, and decided that attempting the summit was worth the danger. If things had gone a little differently, perhaps even she would have been given room to be seen as passionate and courageous.24

While reading about Claude and her expedition, I was reminded of Megan Mayhew Bergman’s 2017 essay on “The Feminine Heroic”– an essay whose core arguments I respectfully disagree with. Bergman’s redemptive approach to female adventure narratives hinges on a number of essentialist assumptions. Bergman writes:

Depicting the feminine heroic has traditionally meant acknowledging the tension between Jungian archetypes—anima (feminine) and animus (masculine)—within a person, and amplifying the masculine traits: leadership, strength, tenacity. Imagine if emotional dexterity and agile compromise were valorized as much as stoicism and physical strength? Nurture over conquest, peace over violence, conservation over exploitation.25

I’m on LeGuin’s side here: I believe these discrepancies are more of a product of socialization than any innate Jungian divergence in the brains of men vs. women. I also don’t think that leadership, strength, and tenacity are necessarily negative traits that women should reject, or that they automatically lead to violence.

Bergman also neglects to thoroughly analyze the colonialist dimensions of the female adventure stories she selects to valorize. She quotes two American mountaineers who describe their travels through Myanmar: “‘It’s a kind of suffering we are privileged to endure,’ she said. ‘We are not living within a war zone or forced to be here … Presence like this is a gift, a really uncomfortable one.’”

I wish that discomfort had been parsed further. Readers may have already picked up on a discrepancy that looms large in the narrative of the Women’s Expedition, but is never addressed directly by the actors involved: the presence of male Sherpas assisting the women in their “all-female” climb, resulting in the deaths of Sherpa Ang Norbu and Sherpa Chewang.

The fact that the participation of Nepalese men in the final summit attempt is never acknowledged by the expedition members or the press is revealing. Implicitly, they did not fully count as men as they were non-European. Claude was also dismissive of a group of female Chinese climbers who claimed to have bested her previous female altitude record by summiting Mustagh Ata in the Pamir Range– tellingly, she argued that they had been assisted by men.26 I’ve searched high and low for more on the eight Chinese women who countered Claude’s record. I’d like to tell a companion story to this one, some day.

With all of these critiques in mind, I’m still deeply affected by Claude and Claudine’s story, and find that it has provoked similar reactions among other exploration history enthusiasts I’ve shared it with. Perhaps the thrill comes from the sheer uniqueness of engaging with a text where women make some of the same mistakes their male counterparts do. There’s a paradoxical freedom to being allowed to participate in a heroic tragedy– even if we as audience members know better than to valorize heroic deaths. The plot beats still resonate. Narratives are powerful things. As an early career historian, it’s a good case study in learning how to approach historical storytelling ethically and critically.

In the foundational text “Mountains of the Mind: Adventures in Reaching the Summit,” Robert Macfarlane deconstructs the idea that the urge to climb is an innate human desire, instead tracing the ways in which Westerners were socialized and conditioned to dream of the mountains. These are the eponymous “mountains of the mind”: not the truth of the thing, but its imaginative potential. Like Macfarlane, I grew up on thrilling historical adventure stories, such as Edward Whymper’s Scramble Amongst the Alps and Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World.27

Macfarlane recognizes these are stories that teach their target audiences, purposefully or accidentally, to want certain things– dangerous things. But what if you’re not a member of the target audience, these books mainly aimed at a young, English male readership? I still think there’s something to be salvaged from the tragedy of the Women’s Expedition to Cho Oyu. For one, it validates the truth I knew since I was young girl, reading chronicles of male heroism: there can be mountains in the minds of women, too. What we choose to do with these phantasms of the colonial imagination is up to us.

Stephen Harper. A Fatal Obsession: The Women of Cho Oyu, A Reporting Saga (Sussex: Book Guild Publishing, 2007). p. 8.

Ibid. p. 9.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Tichy, Herbert. Cho Oyu: By Favour of the Gods. United Kingdom: Methuen, 1957. For more on gendered language in the Himalaya and the colonialist implications of the conquerable “feminine” mountain in the Western gaze, see Sherry B. Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering.

Kogan, Claude and Raymond Lambert, White Fury: Gaurisankar and Cho Oyu, Hurst & Blackett, 1956.

"Woman with Mountain Team That Reaches Himalayan Peak: Paris Dress Designer and Six Men Realize 'Dream Of Every Mountaineer'". Toledo Blade. 9 September 1953. Note: There are varying accounts of Georges Kogan’s cause of death, with Harper reporting it as a bout of illness following an Andean ascent. Contemporary periodical accounts, such as the one cited here, name the cause of death as a climbing accident.

Claudine seems to have left her high society life in Luxembourg after Cayesh and joined Claude in Paris, where she took a job at a salon. It is unclear how much of a relationship they had outside of their mountaineering ventures, one of the many missing puzzle pieces leading up to the genesis of the Women’s Expedition.

Bradsher, Henry S. The Dalai Lama's Secret and Other Reporting Adventures: Stories from a Cold War Correspondent. Louisiana State University Press, 2013. p. 52.

Harper, A Fatal Obsession. p. 11.

Ibid. p. 14.

“Un récit du drame du Cho-Oyu, par Jeanne Franco.” Le Monde, 18 Novembre 1959.

I plan to revisit the material in this article once I track down a copy of Rambaud’s book. Admittedly, one of the challenges of working on this piece is the inaccessibility of certain sources, and the obfuscation surrounding others. In the process of piecing together the background of Harper’s book, I encountered the following mystery in the Top of the World Mountaineering & Polar Books catalog, regarding an earlier published version of Harper’s account named “Lady Killer Peak” from 1965: “This book was revised and expanded in 2007 under the title ‘A Fatal Obsession’. Curiously, this later edition made no reference to the earlier 1965 edition. When I inquired about this the publisher denied that ‘Lady Killer Peak’ existed. An important book on this early expedition and quite hard to find.”

Harper, A Fatal Obsession. p. 15. The undefined “border situation” most likely refers to tensions in the wake of the 1959 Tibetan Uprising, as Cho Oyu lies directly on the modern border between Nepal and Tibet. 1959 was a tumultous year in the region, following one revolt in Tibet and preceding another– the 1960 Nepal Coup D’Etat which overthrew democratic rule and instated Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev as King of Nepal.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 12.

Ibid. p. 53.

Ibid. p. 56.

Ibid.

Martina Gugglberger (2020) ‘Joys of Exploration’: Gender-Constructions in the 1959 Cho Oyu Women’s Expedition, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 37:9, 813-830.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Le Guin, Ursula K.. Words are My Matter: Writings on Life and Books. United States: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019. p. 85.

I also wonder at the nationalist dimensions of her character evaluation– the British Pinnacle Club was especially eager to go along with the press’s critique of Claude’s judgement.

Bergman, Megan Mayhew. “The Feminine Heroic”. The Paris Review, 2017.

Harper, A Fatal Obsession. p. 8.

Macfarlane, Robert. Mountains of the Mind: Adventures in Reaching the Summit. Vinatge Books, 2003. p. 4.